US Dollar (USD) as Reserve currency and its future - Part 1 ⮐

Money is just paper. Until it isn’t.

The US dollar didn’t become the world’s reserve currency by accident. It took three deliberate, strategic moves — each one transforming the rules of global finance while everyone else was still playing by the old ones.

- Move one - Replace british pound

- Move two - Break the gold promise

- Move three - Oil for dollar

How a wartime agreement, a broken promise, and a desert handshake built a monetary empire. This is the story of how the United States engineered monetary dominance — not just through world war military strategies, but through a series of calculated institutional maneuvers that most people have never heard of. And more importantly, what it means for the future of money.

Move One: Replace the British Pound (1944)

Before World War II, the British pound sterling ruled international trade. Britain was the center of global commerce. The pound was as good as gold — literally backed by it. London was where the world’s money flowed.

Then came the war.

Britain went massively into debt. The country sacrificed more than a quarter of its national wealth to fight Germany. Factories were bombed. The treasury was emptied. The empire that once controlled a quarter of the world’s landmass was suddenly a debtor nation, dependent on American loans to survive.

Meanwhile, America emerged unscathed. No bombs fell on Detroit or Pittsburgh. Its factories were running at full capacity, producing tanks, planes, and ships. Its gold reserves were swelling as European nations paid for American weapons and supplies. By 1944, the United States held roughly three-quarters of the world’s monetary gold.

US Gold Reserves 1930-2024

| Year | Gold Reserves (metric tonnes) | Key Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 6,358 | Pre-Depression baseline |

| 1935 | 8,998 | After Gold Reserve Act |

| 1940 | 19,543 | WWII capital flight to US |

| 1944 | 21,800 | Bretton Woods Conference |

| 1950 | 20,279 | Post-war peak |

| 1960 | 15,822 | European recovery begins |

| 1970 | 9,839 | Nixon Shock looms |

| 1971 | 9,070 | Gold window closes |

| 2024 | 8,133 | Present day (stable since 1980) |

Gold Price: From $35 Fixed to Free Float

USD per troy ounce, key events marked

US Gold Reserves: The Foundation of Dollar Power

Metric tonnes held by US Treasury, 1930-2024

In July 1944, as Allied troops were racing across Normandy, 730 delegates from 44 nations gathered at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Their mission: design the post-war financial order.

The British delegation was led by John Maynard Keynes, the most famous economist in the world. Keynes proposed a new international currency called the “bancor” — a neutral unit of exchange managed by a world central bank. It was elegant, fair, and would have prevented any single nation from dominating global finance.

The Americans had a different idea.

Harry Dexter White, the US Treasury official leading the American delegation, proposed a system where all currencies would be fixed to the dollar, and the dollar would be fixed to gold at $35 per ounce. The US would be the anchor. The US would be the center.

“The American dollar thus obtains international recognition, on paper as in fact, as the world currency.”

— New York Times, July 23, 1944

Keynes lost. The Americans won. As Benn Steil wrote in The Battle of Bretton Woods, Keynes had only “his own brilliance and a fast-fading appeal to Anglo-American wartime solidarity.” The Americans had leverage — they had the gold.

The outcome: every country would keep their currency fixed to the dollar, within a 1% band. The dollar was fixed to gold. Central banks could exchange their dollars for gold at any time. The British pound was out. The US dollar was in.

This wasn’t charity. This was strategy.

Move Two: Break the Gold Promise (1971)

The Bretton Woods system worked beautifully — until it didn’t.

The design had a fatal flaw, identified by economist Robert Triffin as early as 1960. To supply enough dollars for global trade, America had to run deficits — spending more abroad than it earned. But running persistent deficits would eventually erode confidence in the dollar’s gold backing. The system contained its own contradiction.

The Triffin Dilemma

The Triffin Dilemma: A System at War with Itself

The paradox that forced the world off the Gold Standard in 1971.

1 To Maintain Confidence

The US must limit dollar supply to keep it strictly backed by gold.

The Crisis: Global trade collapses due to a lack of liquidity (cash).

2 To Fuel Global Trade

The US must run huge deficits to flood the world with dollars.

The Crisis: Gold backing becomes a mathematical impossibility.

⚠️ Result: Inevitable Systemic Collapse

By the late 1960s, the contradiction was becoming reality.

Europe and Japan had rebuilt from the war. Their exports became competitive with American goods. The US trade balance deteriorated. Military spending in Vietnam added to the outflow. Dollars piled up in foreign central banks.

Meanwhile, US gold reserves were shrinking. In 1944, America held 21,800 metric tonnes of gold. By 1970, that had fallen to 9,839 tonnes — a decline of 55%. Foreign governments were quietly exchanging their dollars for gold, depleting America’s reserves month by month.

The country was vulnerable to a bank run — except the bank was the entire United States, and the depositors were foreign governments.

In early August 1971, the British ambassador formally requested that the US guarantee the gold value of $3 billion in British dollar reserves. France had already been aggressively converting dollars to gold for years under De Gaulle’s direction. A run was coming.

From August 13 to 15, 1971, President Nixon and fifteen advisers — including Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns and future Fed Chairman Paul Volcker — gathered secretly at Camp David. They created what they called the “New Economic Policy.”

On Sunday evening, August 15, Nixon went on television:

“I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold.”

— President Richard Nixon, August 15, 1971

“Temporarily” turned out to be permanently. The gold window never reopened. The foundation of the entire international monetary system — the promise that made Bretton Woods work — was unilaterally withdrawn.

The technical term is the “Nixon Shock.”

But here’s what’s remarkable: the dollar didn’t collapse. It strengthened.

Why? Because by 1971, the dollar was already so embedded in global trade that countries had no practical alternative. Contracts were denominated in dollars. Reserves were held in dollars. The infrastructure of international commerce — banking relationships, settlement systems, pricing conventions — all ran on dollars.

Switching would have been catastrophically expensive. The network effects were more powerful than the gold.

Nixon didn’t just break a promise. He revealed that the promise was never the source of the dollar’s power.

Move Three: Oil for Dollars (1973-1975)

After leaving the gold standard, America needed a new anchor. It found one in the desert.

The 1973 oil crisis gave the US an opening. Arab oil producers had just demonstrated their leverage by imposing an embargo on the United States in retaliation for American support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War. Oil prices quadrupled from $3 to $12 per barrel. Gas stations ran dry. The world learned that energy was the ultimate commodity.

In June 1974, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Treasury Secretary William Simon traveled to Saudi Arabia. Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz, the Second Deputy Prime Minister, met with them and President Nixon in Washington around the same time.

The exact terms of what was negotiated remain debated. There was no single document titled “The Petrodollar Agreement.” But the outcome was clear.

Saudi Arabia would price its oil in dollars. In exchange, the US would provide military protection and access to American weapons. The Saudis would also invest their oil revenues — hundreds of billions of dollars — in US Treasury bonds. This recycling of petrodollars back into American financial markets would support the dollar and keep interest rates low.

By 1975, all OPEC nations were trading oil in dollars.

The Petrodollar Flywheel

- Every country needs oil to run their economy

- Oil is priced and traded exclusively in US dollars

- Countries must hold dollar reserves to buy oil

- Oil exporters receive dollars, invest them in US Treasuries

- This demand keeps the dollar strong and US borrowing costs low

- Strong dollar reinforces oil pricing convention

- Cycle repeats — creating persistent global demand for dollars

Think about what this meant. Gold was physical and limited — there was only so much of it in the ground. But oil demand was growing and insatiable. Every new factory in China, every car on the road in India, every airplane crossing the Pacific — all required oil. And all required dollars to pay for it.

The petrodollar system achieved what gold could not: it created growing demand for dollars, linked to global economic expansion itself.

The Larger Pattern

Step back and look at the sequence.

In 1944, the dollar’s strength came from American gold reserves. In 1971, Nixon revealed that the gold was never essential — the network effects were. In 1974, a new foundation was built on oil demand.

Each transition followed a similar pattern:

- Crisis emerges in the existing arrangement

- Unilateral action by the United States changes the rules

- New foundation is established that preserves dollar dominance

- World adapts because switching costs are prohibitive

What’s consistent across all three moves is the strategic insight: the dollar’s power doesn’t come from any single backing, but from its embeddedness in global commerce. Once the dollar became the infrastructure — the plumbing of international trade — it became very hard to displace.

Where We Are Now

The dollar remains dominant, but the landscape is shifting.

Global Reserve Currency Composition 1995-2024

| Year | USD | EUR | JPY | GBP | CNY | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 59% | — | 6.8% | 2.1% | — | 32% |

| 1999 | 71% | 17.9% | 6.4% | 2.9% | — | 1.8% |

| 2001 | 72% | 19.2% | 5.0% | 2.7% | — | 1.1% |

| 2010 | 62% | 26.0% | 3.7% | 3.9% | — | 4.4% |

| 2020 | 59% | 21.2% | 5.9% | 4.7% | 2.1% | 7.1% |

| 2024 | 58% | 20% | 6% | 5% | 2% | 9% |

Global Foreign Exchange Reserves by Currency (2024)

IMF COFER data — USD share declined from 72% peak (2001) but remains dominant

Source: IMF COFER data

Reserve Currency Share Over Time (1999-2024)

Percentage of global foreign exchange reserves by currency

As of late 2024, about 58% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in dollars. The euro holds roughly 20%. The Chinese yuan — despite China being the world’s largest exporter — holds just 2%.

Oil is still overwhelmingly priced in dollars. International debt is still largely denominated in dollars. SWIFT, the messaging network for cross-border payments, still processes most transactions in dollars. The dollar remains the plumbing.

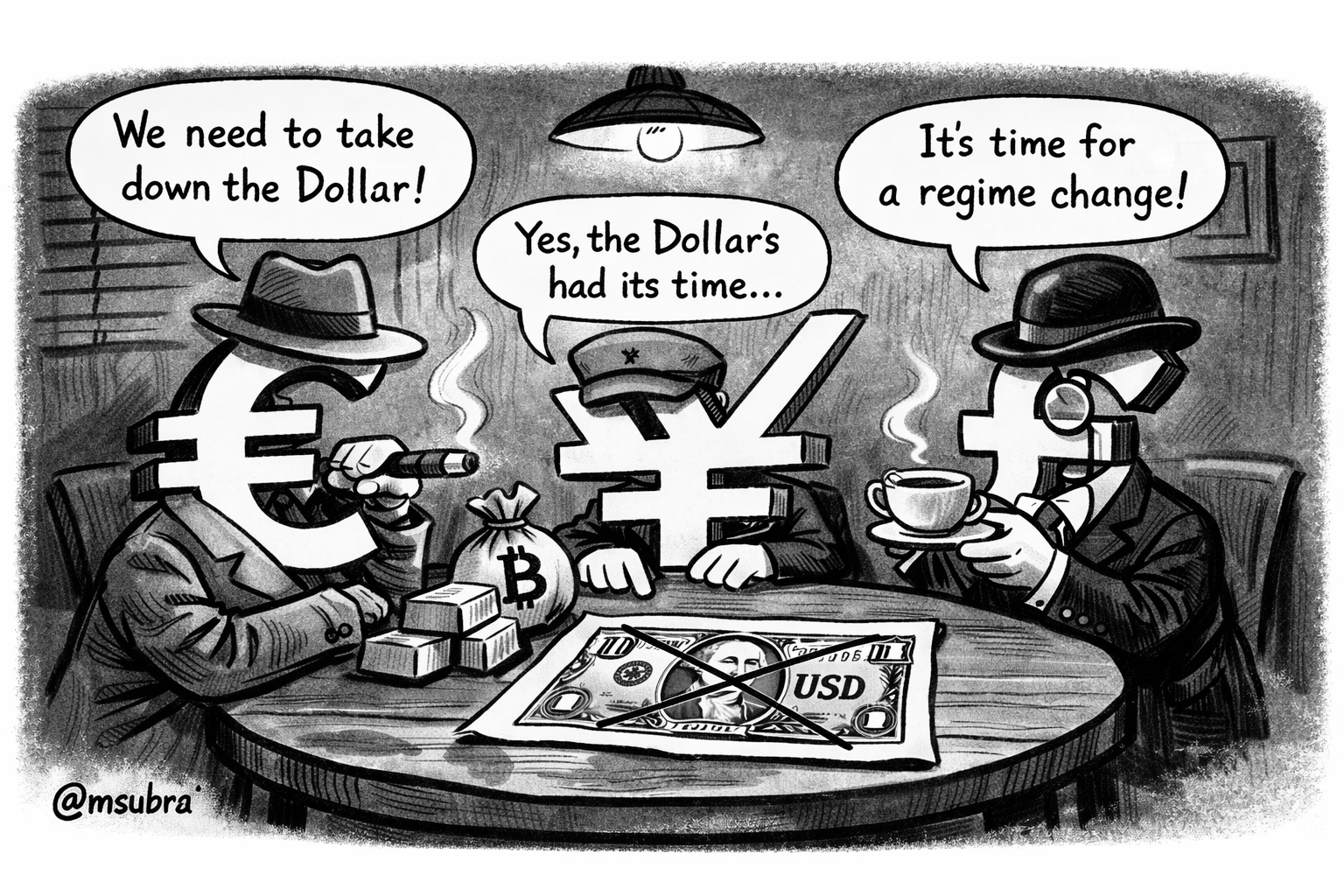

But pressures are building:

Sanctions and weaponization: After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US froze Russian central bank assets. This demonstrated the dollar’s power — but also its risk. Countries are now asking: could this happen to us?

China’s rise: China and Saudi Arabia have discussed oil trades in yuan. BRICS nations are exploring payment alternatives. The mBridge project connects multiple central bank digital currencies.

US fiscal trajectory: American debt has surpassed $34 trillion. If confidence in US fiscal management erodes, dollar holdings become less attractive.

Central bank gold buying: Central banks added more gold to reserves in 2022-2023 than in any period since 1950. Gold’s share of reserve assets has more than doubled since 2015.

Timeline: Eight Decades of Dollar Dominance

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1944 | Bretton Woods | USD becomes anchor of global monetary system |

| 1958 | System Goes Live | Currencies become fully convertible |

| 1960 | Triffin Warning | Economist predicts dollar crisis |

| 1968 | Gold Pool Collapse | Seven nations stop defending $35/oz |

| 1971 | Nixon Shock | Gold window closes permanently |

| 1974 | Petrodollar | Saudi Arabia prices oil in USD |

| 1975 | OPEC Follows | All OPEC nations trade in dollars |

| 1999 | Euro Launches | First potential challenger emerges |

| 2016 | Yuan in SDR | Chinese currency joins IMF basket |

| 2022 | Russia Sanctions | Dollar weaponization debate intensifies |

What Comes Next?

History suggests America will find a fourth move.

The pattern has been consistent: when the current arrangement becomes untenable, someone in Washington engineers a new arrangement that preserves dollar dominance while transforming its foundation. Gold gave way to network effects. Network effects were reinforced by oil. What comes after oil?

Some possibilities:

Digital infrastructure: If the US can position itself at the center of digital payments infrastructure — whether through a digital dollar, stablecoin regulation, or dominance in cross-border payment rails — this could become the next foundation.

Technology standards: Just as oil required dollars, AI, semiconductors, and cloud computing could require American standards and settlement.

Security guarantees: The petrodollar was partly a security arrangement. New security dependencies — cyber defense, space access, supply chain resilience — could create new dollar dependencies.

Or perhaps the fourth move never comes. Perhaps the dollar slowly fades as reserve managers diversify, as regional blocs emerge, as technology enables alternatives. Perhaps we’re watching the end of an era.

But I wouldn’t bet on it.

The dollar hasn’t survived eighty years because of gold, or oil, or any single backing. It has survived because of strategic adaptability — the willingness to remake the rules when the old rules stop working, combined with the leverage to make others accept the new ones.

Paper is just paper. Until someone makes it indispensable.

#USD #Geopolitics #Finance #Payments #History #Economics

Data sources: IMF COFER, Federal Reserve, World Gold Council, St. Louis Fed